UVALDE, Texas (AP) — A Texas judge on Thursday refused to throw out criminal charges accusing the former Uvalde schools police chief of putting children at risk during the slow response to the 2022 Robb Elementary School shooting, while a lawyer for his co-defendant said they want to move the upcoming trial out of the small town where the massacre occurred.

At a court hearing in Uvalde, Judge Sid Harle rejected Pete Arredondo's claim that was he improperly charged and that only the shooter was responsible for putting the victims in danger. Nineteen children and two teachers were killed in the shooting on May 24, 2022.

Harle also set an Oct. 20, 2025, trial date. An attorney for Arredondo's co-defendant, former Uvalde schools police officer Adrian Gonzales, said he will ask for the trial to be moved out of Uvalde because his client cannot get a fair trial there. Uvalde County is mostly rural with fewer than 25,000 residents about 85 miles (140 kilometers) west of San Antonio.

“Everybody knows everybody,” in Uvalde, Gonzales attorney Nico LaHood said.

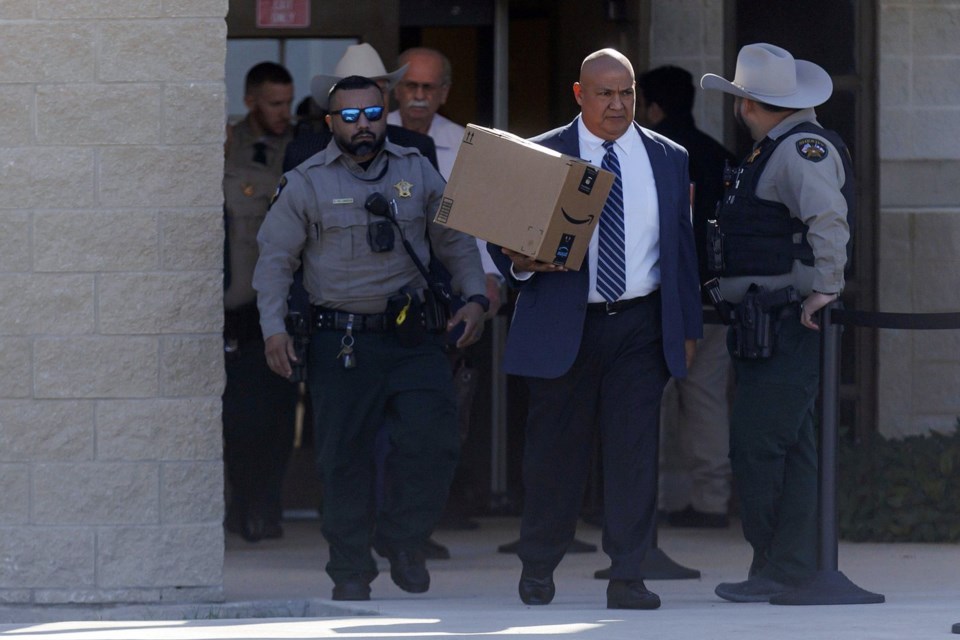

Both former officers attended the hearing.

Nearly 400 law enforcement agents rushed to the school but waited more than 70 minutes to confront and kill the gunman in a fourth-grade classroom. Arredondo and Gonzales are the only two officers facing charges — a fact that has raised complaints from some victims' families.

Both men have pleaded not guilty to multiple counts of abandoning or endangering a child, each of which carry punishment of up to two years in jail. Gonzales has not asked the judge to dismiss his charges.

A federal investigation of the shooting identified Arredondo as the incident commander in charge, although he has argued that state police should have set up a command post outside the school and taken control. Gonzales was among the first officers to arrive on the scene. He was accused of abandoning his training and not confronting the shooter, even after hearing gunshots as he stood in a hallway.

Arredondo has said he was scapegoated for the halting police response. The indictment alleges he did not follow his active shooter training and made critical decisions that slowed the police response while the gunman was “hunting” his victims.

It alleges that instead of confronting the gunman immediately, Arredondo caused delays by telling officers to evacuate a hallway to wait for a SWAT team, evacuating students from other areas of the building first, and trying to negotiate with the shooter while victims inside the classroom were wounded and dying.

Arredondo’s attorneys say the danger that day was not caused by him, but by the shooter. They argued Arredondo was blamed for trying to save the lives of the other children in the building, and have warned that prosecuting him would open many future law enforcement actions to similar charges.

“Arredondo did nothing to put those children in the path of a gunman,” said Arredondo attorney Matthew Hefti.

Uvalde County prosecutors told the judge Arredondo acted recklessly.

“The state has alleged he is absolutely aware of the danger of the children,” said assistant district attorney Bill Turner.

Jesse Rizo, the uncle of 9-year-old Jacklyn Cazares who was killed in the shooting, was one of several family members of victims at the hearing.

“To me, it’s hurtful and painful to hear Arredondo’s attorneys try to persuade the judge to get the charges dismissed,” Rizo said.

He called the wait for a trial exhausting and questioned whether moving the trial would help the defense.

“The longer it takes, the longer the agony,” Rizo said. “I think what’s happened in Uvalde … you’ll probably get a better chance at conviction if it’s moved. To hold their own accountable is going to be very difficult.”

The massacre at Robb Elementary was one of the worst school shootings in U.S. history, and the law enforcement response has been widely condemned as a massive failure.

Nearly 150 U.S. Border Patrol agents, 91 state police officers, as well and school and city police rushed to the campus. While terrified students and teachers called 911 from inside classrooms, dozens of officers stood in the hallway trying to figure out what to do. More than an hour later, a team of officers breached the classroom and killed the gunman.

Within days of the shooting, the focus of the slow response turned on Arredondo, who was described by other responding agencies as the incident commander in charge.

Multiple federal and state investigations have laid bare cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology, and questioned whether officers prioritized their own lives over those of children and teachers. Several victims or their families have filed multiple state and federal lawsuits.

___

Associated Press reporter Jim Vertuno in Austin, Texas, contributed.

___

Lathan is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

Nadia Lathan, The Associated Press